Ask me to rank my top 10 favorite characters in TV history. Gomer Pyle will be in the Final Four playoff, along with Andy Taylor, Barney Fife and Beaver Cleaver.

Ask me to rank my top 10 favorite characters in TV history. Gomer Pyle will be in the Final Four playoff, along with Andy Taylor, Barney Fife and Beaver Cleaver.

Ask me who delivered the definitive version of “The Impossible Dream” with a voice as powerful as a riptide and I will not hesitate to answer Jim Nabors.

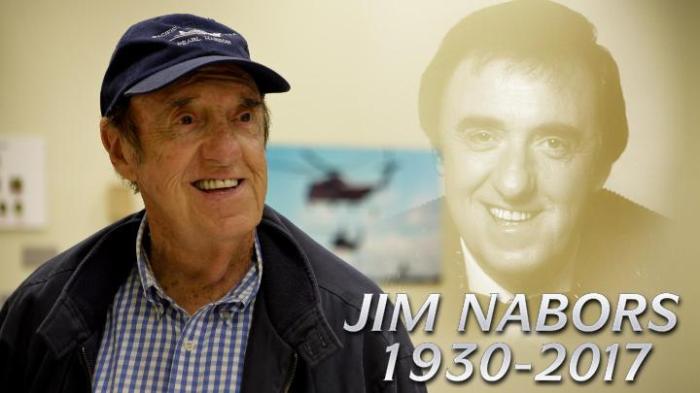

I was spending a recent Thursday morning doing as I was told in helping to set up and decorate our church for our daughter’s Saturday wedding. The news came over Twitter and Facebook that Jim had left us at the age of 87.

This one was like a punch in the gut. The news was another reminder that while characters that strike a chord in our lives through television are immortal, the people who play them are not.

I actually saw Jim Nabors perform for the first time in 1961. My family had just moved to Waycross, Ga., then the home of what one national magazine described as one of the 15 worst cities in America for television reception. Unless one had a prohibitively expensive high-gain antenna, the choice was WJXT in Jacksonville or nothing. Jacksonville had two affiliates but one of those spring thin air nights to pick up the NBC station, WFGA. Both channels cherrypicked ABC programs.

WJXT opted on Wednesday nights to snag The New Steve Allen Show, a comeback bid for The Tonight Show originator. Steve’s show was up against television’s number one show, Wagon Train, and failed to last. However, a young singer named Jim Nabors appeared on several shows. He could belt out a tune with a powerful baritone. My parents enjoyed him. However, with the short life of Steve’s variety hour, Jim faded into the woodwork as did scores of other performers who tried to break into early sixties television.

A little more than a year later, the Christmas Eve episode of The Andy Griffith Show was entitled “The Bank Job.” Barney Fife set out to prove that The Mayberry Bank was a crime pushover. A local mechanic who had never been introduced, Gomer Pyle, appeared. Gomer had a voice that sounded as if he had done a dozen lube jobs in a  day. Bit characters came and went in Mayberry, most never again to be seen. Somehow, Gomer grabbed our attention. I remember my father laughing uproariously at the few lines Gomer delivered. We thought little more about it the next day—but Andy Griffith and his producers did.

day. Bit characters came and went in Mayberry, most never again to be seen. Somehow, Gomer grabbed our attention. I remember my father laughing uproariously at the few lines Gomer delivered. We thought little more about it the next day—but Andy Griffith and his producers did.

Jim had no idea the 23 episodes in which he appeared on The Andy Griffith Show would propel him into major stardom. This is a guy who just 10 years earlier had been a camera operator, film editor and morning show host at WJBF in Augusta.

The episode of December 16, 1963, was arguably the major turning point in the 33-year-old Nabors’ career. Directed by actor Richard Crenna, “Citizen’s Arrest” became a signature episode of The Griffith Show‘s middle years. Frustrated after Barney wrote him a ticket for making a U-turn in the middle of the town square, Gomer catches Barney doing the same thing. The Mayberry mechanic begins yelling, “Citizen’s array-ust! Citizen’s array-ust!” The next three minutes of confrontation between Gomer and Barney were sheer comic genius. Crenna never received the full credit he deserved for staging that scene.

I knew that episode hit home. For the next two weeks during my school’s Christmas holidays, I encountered people everywhere—-including myself—-shouting “citizen’s array-ust!” Along with “nip it in the bud,” Floyd’s “oooooh, Annnnndy” and Barney’s classic “Juanita? Barn….cock-a-doodle-doooooo,” Gomer’s revenge became one of the ten charismatic catchphrases in the history of the series.

Spinoffs were still fledgling elements of television in the mid-sixties. Harry Morgan’s character of Pete Porter was spun off into Pete and Gladys, a CBS sitcom derived from fifties favorite December Bride. The characters of Bronco Layne and Sugarfoot were introduced on ABC’s Cheyenne but not expanded into their own rotating series until Clint Walker engaged in a contract dispute with Warner Brothers over merchandising and salary from Cheyenne. In 1956, The $64,000 Challenge was a spinoff from the megahit The $64,000 Question to exploit the popularity of winners on Question. Andy Griffith’s own series was introduced as a one-shot pilot on The Danny Thomas Show but the ensemble characterizations had not been developed.

The evening of May 18, 1964, was the moment of truth for the character of Gomer Pyle. Gomer enters the sheriff’s office and does a choreographed version of The Marine’s Hymn. Andy watches and says, “That’s real good, Gomer.” Quickly, Gomer tells his friend, “Andy….I’m in.” “In” was his enlistment papers in the United States Marine Corps.

Andy watches and says, “That’s real good, Gomer.” Quickly, Gomer tells his friend, “Andy….I’m in.” “In” was his enlistment papers in the United States Marine Corps.

In the following 27 minutes, we had a preview of what would take over sitcom television the following season. Gomer as a bumbling Marine only embellished his personality as the bumbling mechanic from Mayberry. We also saw how the chemistry would build between Nabors and one of the most underrated supporting actors in sitcom history, Frank Sutton. Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. could not have been possible without Jim’s talent but the series would also not have worked without the counterpoint of Sutton as the beleaguered Sergeant Vince Carter. When the two stood nose-to-nose after Gomer’s initial faux pas, you knew a winner was on the way.

Contrary to information in some of Nabors’ obituary tributes, CBS had already decided to pick up Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. as a series well before the pilot aired. In those days, the network fall lineups were locked in as early as Washington’s birthday. Network executives screened producer-writer Aaron Ruben’s pilot and immediately gave it the green light. CBS intentionally saved its airing until the final Griffith episode of the 1963-64 season.

Ironically, TV Guide—in its fall forecasts—did not see great hope for Pyle. The prediction was for a middle-of-the-pack rating. Indeed, the time slot would be a challenge. CBS had not experienced exceptional success with sitcoms on Friday nights through the years. Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. would go in Fridays at 9:30. The lead-in was a new but highly-touted ensemble variety hour The Entertainers starring Carol Burnett, Bob Newhart and a cast of up and coming singers and comics. The lead-out, Slattery’s People, was a high-concept drama starring Richard Crenna in his first serious role as a state legislator.

The biggest battle for Gomer would be the series’ competition. After CBS network president Jim Aubrey abruptly canceled The Jack Benny Program after 14 years (the book CBS: Reflections in a Bloodshot Eye quotes sources as saying Aubrey cruelly told the legend, “You’re through.”), NBC picked up Benny for the Friday at 9:30 half-hour. Benny promised to feature younger guests (The Smothers Brothers, The Lettermen, Peter, Paul and Mary, Jack Jones) as well as TV heavyweights Lucille Ball, Bob Hope and George Burns. ABC countered with 12 O’Clock High, an hour-long war drama based on the movie of the same title. The betting line was the Benny would be tough sledding for Gomer if his audience followed him to NBC.

Until the 1975-76 season, Nielsen ratings were based on two-week averages. The first Gomer Pyle episode featured a solid premiere as Gomer was inept trying to navigate the obstacle course but worked extra time at night until he succeeded. Week two fleshed out some of Gomer’s fellow recruits as a platoon member’s girlfriend managed to sneak into the barracks. The verdict was a stunner for the handicappers. Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. was immediately CBS’s number one show, finishing third for the two-week period behind NBC’s Bonanza and ABC’s Bewitched. Twelve O’Clock High was 59th but the shocker was the result for The Jack Benny Program. Out of 100 network series, the legend from Waukegan was in 97th place. CBS indeed appeared to be right in canceling him.

in case the early ratings were a fluke, CBS sent Nabors on a promotional swing as he appeared on Art Linkletter’s House Party and the prime time version of To Tell the Truth. Regular panelist Orson Bean was given the week off from Truth in order to bring Nabors to the popular game show’s panel October 26, 1964. For a week in a blitz of heavy daytime promos, voiceover announcers touted the star of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. as joining the panel of stars (Tom Poston, Peggy Cass and Kitty Carlisle). Jim was a bit nervous. He never before had played on a game show. Onstage with heavyweight veterans Poston, Cass and Carlisle, the Alabama native struggled to ask pertinent questions of the contestants. Only two games were played rather than the usual three because the episode was cut to 25 minutes to accommodate a five-minute political talk for the upcoming Presidential election.

in case the early ratings were a fluke, CBS sent Nabors on a promotional swing as he appeared on Art Linkletter’s House Party and the prime time version of To Tell the Truth. Regular panelist Orson Bean was given the week off from Truth in order to bring Nabors to the popular game show’s panel October 26, 1964. For a week in a blitz of heavy daytime promos, voiceover announcers touted the star of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. as joining the panel of stars (Tom Poston, Peggy Cass and Kitty Carlisle). Jim was a bit nervous. He never before had played on a game show. Onstage with heavyweight veterans Poston, Cass and Carlisle, the Alabama native struggled to ask pertinent questions of the contestants. Only two games were played rather than the usual three because the episode was cut to 25 minutes to accommodate a five-minute political talk for the upcoming Presidential election.

As a testament to CBS’ promotional machine and Nabors’ increasing popularity resulted in the highest rating of the 11 years of nighttime To Tell the Truth. The episode scored a 26.4 rating and 42 percent share of audience, crushing the NBC and ABC competition.

As a testament to CBS’ promotional machine and Nabors’ increasing popularity resulted in the highest rating of the 11 years of nighttime To Tell the Truth. The episode scored a 26.4 rating and 42 percent share of audience, crushing the NBC and ABC competition.

The numbers for Gomer Pyle were no fluke. They not only held up but increased week-to-week. For the full 1964-65 campaign, Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. averaged a 30.7 rating, finishing in a virtual tie with Bewitched (at 31.0). For the final 14 weeks of the season, Gomer overtook Bewitched to become number two overall.

Jim Nabors was no longer a solid supporting actor. He was morphing into a major network television star. His musical talents were incorporated into two episodes of the first season. He recorded his first album for Columbia Records, Shazam!, based on the Captain America yell he comedically incorporated in Mayberry and on the Marine base. The first recording was in Gomer’s country voice. That was followed up with By Request, which featured Nabors doing a number of Broadway and movie standards in his operatic style. A third LP, Jim Nabors Sings: Cuando Calienta el Sol, went gold.

During the five years of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C., more elements of Gomer’s family were expanded. He frequently quoted from Grandma Pyle (“Sergeant Carter, Grandma Pyle says you should chew your food 12 times before you swaller it.”). We met his cousin Bridey and his grandfather. He dated a colonel’s daughter and two Hollywood stars (one of them Ruta Lee). He gained a steady girlfriend in off key nightclub singer Lou Ann Poovie (played by the incomparable Elizabeth MacRae). He gave Vince constant nightmares, including one literally in a hilarious episode during which a meal of Welsh rarebit made Gomer and Vince both dream they had switched personalities.

A favorite Gomer Pyle episode was one in which Gomer was entrusted with Vince’s car while the sergeant was dispatched to collect an AWOL Marine. The vehicle was stolen. Eventually, it lands on a construction site where the car is destroyed. The outstanding character actor Ken Lynch, whose TV career went back to the days of DuMont as The Plainclothesman, played the police sergeant who felt a sense of empathy for Private Pyle. My daughter, watching the episode in rerun as a small child, went around the house for days chanting Gomer’s lament, “Sergeant Carter’s goin’ to kill me. He’s gonna kill me dead!” The construction company owner agrees to replace Carter’s car. A classic line toward the end comes when Gomer explains to Vince: “This big ball fell on it and smashed your car to Smithereens!” Every time I saw a similar device when my university’s library was built three years ago, I kept thinking, “This big ball’s going to fall down and smash somebody’s car to Smithereens!”

The writers looked for more openings to incorporate Jim’s vocal talents into the series. The most memorable musical moment came in episode nine of the fourth season. During the November rating sweeps, Gomer won a singing contest. The prize: a trip to sing before an elite audience at a Washington, D.C., concert. Nabors had already sung “The Impossible Dream” from “Man of LaMancha” on The Danny Kaye Show and the premiere episode of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967. The arrangement in which Jim was accompanied by the U.S. Marine Corps Band was unmatched. People have been tweeting and spreading that version on Facebook in the hours after we learned of Nabors’ death. I don’t care how many times I hear it, Jim’s powerful delivery still gives me chills.

During its five seasons, Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C., never finished lower than tenth in the Nielsens (and that was in year three when CBS moved the show to Wednesday nights). The series was invincible. Back on Friday nights at 8:30, Gomer finished the first month of the 1968-69 season as the number two show in the Nielsens, runner-up only to NBC’s juggernaut Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. At that point, TV Guide reported that Jim was thinking out loud about doing a weekly variety hour in 1969-70. CBS was still non-committal. With the numbers Gomer was still pulling, the network was willing to offer a Brinks truck for Nabors to do two more years of the sitcom.

Jim had other numbers on his side. In November 1965, The Andy Griffith Don Knotts Jim Nabors Show, a variety special, went through the roof in the Nielsens. In 1967, American Motors sponsored Friends and Nabors, Jim’s first solo special, with guests Griffith, Tennessee Ernie Ford, opera star Marilyn Horne and Shirley Jones. The following year in what would be a fortuitous Thursday at 8 slot, Jim hosted Girl Friends and Nabors. As a finale, Nabors sang an old Ernest Tubb song rearranged with a big band sound, “Tomorrow Never Comes,” which drew a huge audience reaction.

Gomer Pyle, USMC, had been a far bigger success than even the best of network prophets could have forecast. Yet, Jim was tired. Because of the interaction required, he was in virtually every scene. Back home at night, he had to learn an additional 14 pages of dialogue. Five years of the grind was taking a toll.

With his nightclub and recording career taking off, Nabors conferred with his manager Dick Linke. As reported in TV Guide, Linke advised: “Jim, with your talents, better to gamble now.”

When the fall 1969 CBS lineup was released in April, Gomer Pyle was not on the schedule. The Jim Nabors Hour was. The original plan was to go Fridays from 8 to 9 on the same night that Gomer had been such a huge success. The popular Hogan’s Heroes would return for a fifth season by moving to 7:30. However, CBS opted late in the scheduling game to go pick up the declining Get Smart from NBC for a sixth season and give a reluctant pickup to The Good Guys, a Bob Denver-Herb Edelman comedy that limped in the Nielsens in its first season. Those comedies were penciled in at 7:30 and 8. Hogan remained at 8:30.

When the fall 1969 CBS lineup was released in April, Gomer Pyle was not on the schedule. The Jim Nabors Hour was. The original plan was to go Fridays from 8 to 9 on the same night that Gomer had been such a huge success. The popular Hogan’s Heroes would return for a fifth season by moving to 7:30. However, CBS opted late in the scheduling game to go pick up the declining Get Smart from NBC for a sixth season and give a reluctant pickup to The Good Guys, a Bob Denver-Herb Edelman comedy that limped in the Nielsens in its first season. Those comedies were penciled in at 7:30 and 8. Hogan remained at 8:30.

CBS looked at the success of two Nabors specials on Thursdays at 8. Further, after two CBS affiliates experienced success with Family Affair on a delayed broadcast Thursdays at 7:30 in 1968-69, the network opted to move the Brian Keith-Sebastian Cabot hit into that time slot as a lead-in for The Jim Nabors Hour. The decision was inspired.

In a future blogpost, we will explore the detailed two-year history of Jim’s variety hour. With a premiere episode that featured Andy Griffith and up-and-coming singer Julie Budd (along with a cameo by Don Knotts), the first week results were impressive. The Sept. 25, 1969, debut scored a 26.0 rating and finished fourth for the week. Family Affair drew higher ratings than its traditional Monday night slot.

Some guests were better draws than others. However, The Jim Nabors Hour finished 11th for the season in the 1969-70 Nielsens. The following season, tougher competition from NBC’s new The Flip Wilson Show weakened the ratings. Nonetheless, the Nabors show was still 28th in 1970-71 and was primed for a third season renewal.

What has unofficially been labeled The Great Rural Purge led to what many observers believed was a premature end for The Jim Nabors Hour. Madison Avenue advertising agencies were pressuring the networks to end a decade of rural appeal shows launched by The Beverly Hillbillies in 1962. Ad executives wanted more dramas, more shows with urban appeal in the large population centers and more programs appealing to the 18-49 age bracket that was viewing song-and-dance hours in fewer numbers. The Nabors show was one of the final casualties on the CBS lineup for 1971-72.

Ironically, Jim was still in demand as a guest star on the remaining CBS variety shows during the seventies. He continued his “good luck charm” appearances on every season premiere of The Carol Burnett Show until its end in 1977-78. He showed up on Tony Orlando and Dawn, The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour and the final season of The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour. A syndicated Nashville-based Music Hall America welcomed Jim as a host.

In 1977, Jim subbed for Dinah Shore on her daytime 90-minute talk/variety series. So impressed were Dinah’s producers that they developed a similar one-hour format for Nabors. In January 1978, The Jim Nabors Show premiered on 140 stations, including WCBS in New York. Many of those stations slotted Nabors opposite the fast-rising Phil Donahue in an early morning time period. After a strong first two weeks, Jim’s ratings began to sag. By the end of the 14th week, his distributor announced The Jim Nabors Show would end after 26 weeks.

Jim never did another series. In 1981, he frontlined a Christmas  special, Jim Nabors’ Christmas in Hawaii, which included him singing Silent Night at Pearl Harbor. His most frequent annual appearances, which started in 1969, were at the Indianapolis 500 where he offered the emotional state song “Back Home in Indiana” for 36 years until a farewell in 2014.

special, Jim Nabors’ Christmas in Hawaii, which included him singing Silent Night at Pearl Harbor. His most frequent annual appearances, which started in 1969, were at the Indianapolis 500 where he offered the emotional state song “Back Home in Indiana” for 36 years until a farewell in 2014.

The fact that a native of middle Alabama could be propelled into near-overnight success as a small town mechanic-turned-Marine private is one of the genuine folklore tales of television. The day of his death, Jim Nabors’ version of “Impossible Dream” from Gomer Pyle, USMC, went viral online. More than one person reacted in the sixties with the phrase, “That voice just doesn’t go with that face.” Indeed, it did.

I enjoyed Gomer because I knew people like him in my hometown. I was an unabashed fan of Jim’s music because our vocal range was similar and his versions of Broadway showstoppers and contemporary middle-of-the-road favorites of the era connected with me. His variety hour was a weekly appointment for me because Jim was himself, not a craft of handlers or managers who wanted him to fit into a pattern.

Most of us never met him but never heard a cross word about him from those who did. For most of the sixties when Jim Nabors appeared either in character of singing a powerful showcloser, we watched—and we wanted more.